During the 17th Annual Seminar on Patient-Physician Relations held by the Technion’s Faculty of Medicine:

“Transgender patients are still met with hostility, belittlement and vast ignorance by the medical establishment.” Thus said researchers during the 17th Annual Prof. Aaron Valero Memorial Seminar on Patient-Physician Relations. Prof. Aaron Valero was one of the founders of the Rappaport Faculty of Medicine at the Technion.

The seminar, which took place in the Faculty of Medicine, focused on a very unique community – people who turn to psychiatrists and surgeons despite being of sound mind and body. This is the community of transgender people – persons born into bodies that are not the “right body” for them. “Nature betrayed us,” in the words of Paola, a young transgender woman who spoke to the audience about her experiences and her coping with the medical system.

“We as doctors must understand who these people are, what their feelings are and what their expectations from us are,” said the moderator, Dr. Rabinovitch. “In contrast to a homosexual, who can begin to live his new life the moment he admits to his orientation or at the moment when he “comes out of the closet”, a transgender person needs medical assistance in realizing the physical change in his body to which he aspires. And we, physicians, do not always know how to “deal” with him, how to talk to him; is it a him or a her?”

Nora Greenberg, a gender specialist who consults to the transgender community, said that these people experience gender incongruence given that their gender identity does not match their bodies and their sexual organs. “This gap causes great distress, which impacts on the person’s life and prevents him from living a full life. The only way to relieve this distress is to expose the real gender emotions and live according to them. Since the body is an important part of their identity experience, and primarily their sexual identity experience, it is no wonder that many transgender people want to change it in order to acquire the characteristics of the gender with which they identify. To do this they require physicians and medicine.”

Ms. Greenberg said that it is very important that the physician address his transgender patient in language that matches the patient’s independent gender designation. “Ignoring the patient’s independent designation positions the physician and the patient on two sides of a power divide. This is an aggressive action that negates not only the patient’s gender identification feelings, but also destroys any chance for a therapeutic relationship based on mutual respect and trust. The person coming to us is someone who is uncomfortable in his present body – his body is essentially his problem. Therefore, as those who are going to treat this body and change it, we must be very sensitive in our discussions with the patient and the treatment itself. First of all, we must ask him which gender we should use to address him (male/female), and respect his answer. We must talk to the person – and not to his present body.”

Following the lecture by Ms. Greenberg, A., a young medical student who has just finished his sixth year of studies, came up to speak. He told his life story. “I have an older sister and a younger sister and we were always called “the girls.” This really bothered me but I did not understand why. In school a soccer club opened but the coach wouldn’t allow me to play – ‘it’s only for boys’, he said. At the age of 16, when my girlfriends talked about setting up a home, I felt somewhat uncomfortable. They didn’t understand why, and in reality, I also didn’t understand.

“Today I am 30 years old. At the age of 23 I heard for the first time the term transgender from a transgender person. Suddenly someone put into words what I had been feeling all my life – that I am not in the right body. It is immensely lonely to live without understanding, without having the words to describe what you feel, without being able to explain. This meeting changed everything.

“Today it is clear to me who I am. I did not need a doctor to agree with this diagnosis. But this discovery was just the beginning of the way. I gradually told my friends and family, and after the fact, it was clear that it would have been a lot easier for them to accept an announcement that I had cancer. The dissonance, the gap between my wonderful self-discovery and society’s reaction, was not easy.”

“And then – the medical procedures: a meeting with my family doctor, a psychiatrist, an endocrinologist. The surgical procedure. These meetings were very difficult – each doctor, each nurse and each medical secretary were sure that it was ok for them to ask every kind of question, invasive as it may be. “How did your parents react? How does your girlfriend feel about the surgery?” – these are questions that would never be asked in any other patient-medical staff encounter. There were also wonderful physicians along the way, but the antagonism, the ignorance and the voyeurism were very hard. These people did not understand how sensitive we are to our body – because it is our problem. If we were innocent souls, without bodies, we wouldn’t have any problem.”

“The medical community, in general, relates to these kinds of people as a curiosity,” said Ms. Greenberg. Correct relations between patients and their doctors require an entirely different kind of connection, the center of which is respect for the person – even if this is the middle of the nightshift in the Emergency Department. These people are not ill and are not disturbed – they come to us because they are suffering a dissonance (a gap) between their bodies and their identity. Our job is to help them on the physical level, without harming them.

“The present definition of the ‘problem’ of these people is Gender Identity Disorder,” said Ms. Greenberg. “I am happy to say that in the soon-to-appear next edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published by the American Psychiatric Association, the definition will be changed to Gender Dysphoria, with the definition of the disorder relating to the distress caused by the lack of sexual congruence, and not to the cross-gender gender identification itself.

“Transgender people have suffered a lot from the pathologization of their identity. Over the past few years, we are seeing a growing trend of de- pathologization, one of whose expressions is the above mentioned change in the DSM. In the past, medicine has tried to oversee the treatment of these people through conservative and rigid treatment models into which patients were supposed to fit. In the last few years, with the establishment of the transgender model with its many facets, a more open treatment approach has become accepted, with many options, and with the treatment being offered changing from patient to patient in response to their needs.

“In general, the historical process is moving in a positive direction: the perception whereby a person must prove that he is an ‘authentic’ transgender person is changing into an understanding that gender identification is not dichotomous (male or female, without any state of in-between) but rather a continuum with, at one end, pure femininity and at the other end, pure masculinity. No real person exists at either of these two extremes – we are all somewhere in between.

“Despite these positive developments, transgender patients still face hostility, belittlement and immense ignorance on the part of the medical establishment. The basic problem is the existing gender conformity, and the fact that most physicians belong to the ruling majority, that is, the cisgender population – people who are not transgender and identify with the gender into which they were born. Like many of the cisgender population, doctors also suffer largely from transphobia – hatred, disgust and fear of transgender persons or abound with the cis-normative approach, that is, the belief that the cisgender identity is natural, healthy and better than transgenderism and every divergence from it is a type of deviation.

“The stage most necessary on the way to change is the understanding by every doctor that he or she belongs to a social system. There is no purely individual person. Therefore, if the doctor belongs to the ruling group, the cisgender group, he must be aware of this, because his behavior is affected by this affiliation. In the next stage, he must be prepared to waive his power as a cisgender person, not his power and knowledge as a doctor – these are essential – but his feelings of superiority, of which he is usually unaware, which do not enable him to understand the patient as a whole and real person.”

In addition to Nora Greenberg and A., another two transgender people who underwent surgery to change gender and life their lives in line with the feelings of their authentic gender identity spoke: Paola, a psychology graduate, and Shamai, a rabbi and social activist, told the audience about their experiences with doctors.

The late Prof. Aaron Valero, a founder of the Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, was born in Jerusalem in 1913 and died 11 years ago. After completing his studies at Gymnasia Yerushalyim (1932), he went to Birmingham, England to study medicine. With the outbreak of World War II he returned to Israel and then served with the British Army in the Persian Gulf. At the end of the war he returned to Israel, moved to Haifa and worked at Poriya Hospital and Rambam Hospital where he set up the Department of Internal Medicine.

Following the decision to establish a medical school at the Technion, Prof. Valero founded the first course “Introduction to Internal Medicine – Physical Diagnosis”, and he was the first to teach the course in reading ECGs. Prof. Rosalie Bar said that Prof. Valero “was an outstanding doctor, an exceptional clinician, introverted and modest, who ran his department primarily by being a role model. He was an exemplar of gentlemanly patient-physician relations, as he had been taught in Birmingham.”

For his continuing activities in strengthening ties between Israeli and German scientists

For his continuing activities in strengthening ties between Israeli and German scientists

For his continuing activities in strengthening ties between Israeli and German scientists

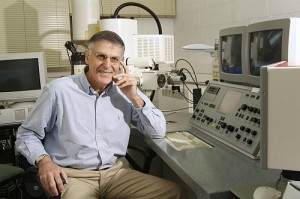

For his continuing activities in strengthening ties between Israeli and German scientists The whole of the Technion celebrated last weekend with Nobel laureate, Distinguished Prof. Danny Shechtman, who leaves next week for Stockholm for the award ceremony. “Our delight is not just because one of our own won the world’s most esteemed prize but, rather, because scientific truth won,” said Technion President, Prof. Peretz Lavie.

The whole of the Technion celebrated last weekend with Nobel laureate, Distinguished Prof. Danny Shechtman, who leaves next week for Stockholm for the award ceremony. “Our delight is not just because one of our own won the world’s most esteemed prize but, rather, because scientific truth won,” said Technion President, Prof. Peretz Lavie. The Technion and Monash University of Australia have launched a series of joint lectures, facilitated by the installation of advanced multimedia equipment by TNN Telecom. Monash University is the largest university in the southern hemisphere.

The Technion and Monash University of Australia have launched a series of joint lectures, facilitated by the installation of advanced multimedia equipment by TNN Telecom. Monash University is the largest university in the southern hemisphere.

NEW YORK CITY/HAIFA, ISRAEL – Cornell University and The Technion – Israel Institute of Technology announced today a new partnership to create a world-class applied science and engineering campus in New York City, as outlined by Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

NEW YORK CITY/HAIFA, ISRAEL – Cornell University and The Technion – Israel Institute of Technology announced today a new partnership to create a world-class applied science and engineering campus in New York City, as outlined by Mayor Michael Bloomberg. October 5, 2011 – Distinguished Professor Dan Shechtman of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Of the five Israeli scientists to have ever won the Nobel Prize, three are Technion professors.

October 5, 2011 – Distinguished Professor Dan Shechtman of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Of the five Israeli scientists to have ever won the Nobel Prize, three are Technion professors. Receive $20,000 & go on to the finals to be held in November in the U.S.

Receive $20,000 & go on to the finals to be held in November in the U.S.