Deep purple at the Technion

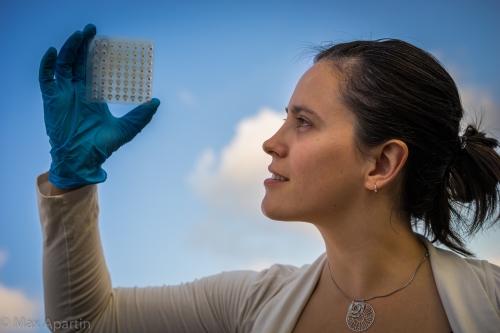

Research conducted at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology has, for the first time since 1971, uncovered a new light sensing protein family. The research – published this week in Nature – was conducted by PhD student Alina Pushkarev under the supervision of Professor Oded Beja, and included collaboration with Japanese, American and Israeli researchers.

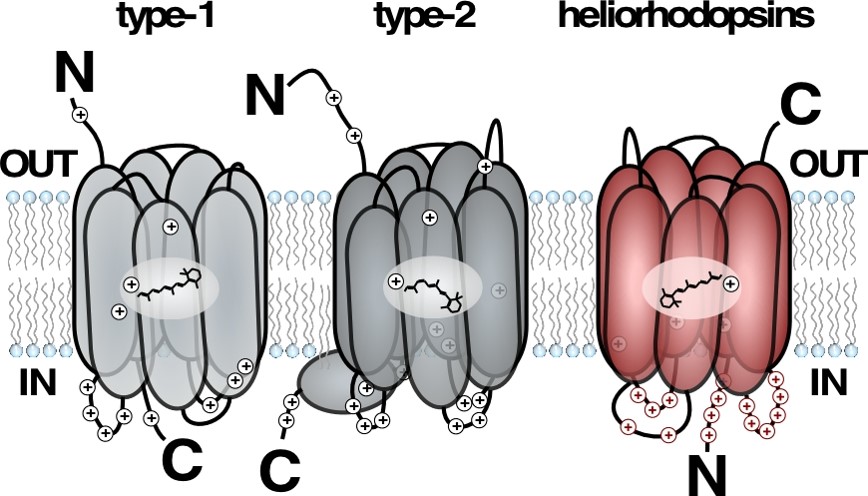

A model describing the transmembrane orientation of previously known rhodopsins (described in grey), showing the 180 degrees flip of the new heliorhodopsin. (Illustration: Oded Béjà)

Light reactive proteins allow living organisms to harvest the energy of the sun. These proteins are responsible for light harvesting by two distinct biological processes. The first of these processes is photosynthesis, which is utilized by plants, algae and aquatic bacteria (cyanobacteria). The second is via retinal bound proteins (rhodopsins), which are utilized by many microorganisms, as well as animal visual organs (including human eyes). Rhodopsins are embedded in the membrane of the cell, by crossing it seven times (i.e. they are a long protein “stitching” the cells’ outer wall seven times). Rhodopsins are comprised of a protein attached to a vitamin A derivative, called retinal, allowing them to capture light.

Currently there are two known rhodopsin types. Microorganisms use Type 1 rhodopsins to sense light and convert it to chemical energy, while Type 2 rhodopsins are found in animal eyes, and crucial for vision.

In the Technion marine microbiology lab, researchers aimed to discover completely new rhodopsins in the microorganisms residing in Lake Kinneret at the peak of summer – when the environment would be well sunlit. Lake Kinneret, like any natural environment, has an abundant variety of microorganisms that cannot be grown in a laboratory. So, Mrs. Pushkarev and Prof. Beja used a laboratory strain of E. coli as a protein factory for expression of the proteins belonging to the microbial residents of Lake Kinneret.

By adding retinal (a form of vitamin A that is the chemical basis for animal vision) to the growth media, the researcher found a gene that turned E. coli to a deep purple color. The gene turned out to be a completely new family of rhodopsins, which are embedded in a completely opposite orientation compared to all other known rhodopsins. Though this rhodopsin family was found to exist in almost all known marine and freshwater environments, it had never before been discovered, despite extensive research of these environments. The researchers named the new family heliorhodopsins (hḗlios, ‘sun’).

The first rhodopsins (Type 2) were discovered in 1876 by the German scientist Franz Christian Boll, who isolated them from frogs. In 1971, almost a 100 years later, researchers from the University of California discovered a new family of rhodopsins (Type 1), in a microbe from hypersaline waters. Their motivation was to explain the purple nature of the Haloarchaea (a salt dwelling archaea) living in these waters.

Three decades later, this seemingly non-medical oriented discovery would lead to the development of a new field in neuroscience: Optogenetics. This field is based on the use of Type 1 rhodopsins, for the controlled excitation of neurons, and even single neurons in mammals.

Today, many research groups in this field are working on the utilization of Type 1 rhodopsins in neuronal disease, correction of cardiac rhythm and more. Now, Mrs. Pushkarev and Prof. Beja’s discovery of a new family of rhodopsins could become the newest tool in the field of optogenetics.

Click here for the paper in Nature